In this article, we investigate single-reaction gas-phase equilibria; specifically, we show how one can easily determine the equilibrium composition with knowledge of the equilibrium constant K. As the student surely knows, any typical chemical reaction can be represented by the general notation

where is a placeholder for the formula of a chemical species and

is a stoichiometric coefficient. The symbol

itself is a stoichiometric number, and by the sign convention adopted in most textbooks, it is associated with a positive sign (+) for a product or a negative sign (-) for a reactant. For instance, in the reaction studied in Example 1 below,

the stoichiometric numbers are

The number of moles of a given reactant/product is related to the stoichiometric number by an expression of the form

where we have introduced a variable , known as the reaction coordinate, which describes the extent or degree to which a reaction has taken place. Integrating the relation above gives

Summation over all species yields

The mole fractions of the species present are expressed as

In a gas-phase reaction, the molar fractions, the system presure, and the so-called equilibrium constant are related by an expression of the form

Here, is the molar fraction of component i,

is the fugacity coefficient of component i,

is the stoichiometric coefficient of species i,

is pressure,

is the reference pressure (usually taken as 1 bar),

is the reaction stoichiometric number, and

is the equilibrium constant. For ideal gases, the fugacity coefficient equals unity and the equation simplifies to

In words, the scary product on the left-hand side simply means that we should multiply in series the molar fractions of each component i, taken to a power equal to its stoichiometric coefficient. Consider, for instance, the simple equilibrium

Here, has a stoichiometric number

= -1 and

has

= 1. Denoting by

the molar fraction of dinitrogen tetroxide and by

the molar fraction of nitrogen dioxide, we write

The molar fractions can be shown to be

so that

Clearly, determining the extent of reaction becomes a matter of evaluating the equilibrium constant K. This quantity is expressed in terms of the reaction change in Gibbs free energy as

The value of at the reaction temperature T can be estimated with the relation

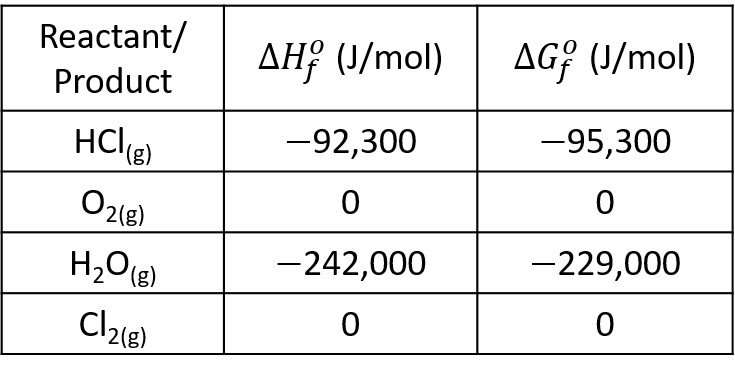

Here, subscript “0” denotes a quantity expressed at the reference temperature , usually 298 K. Given the heats of formation

and the change in Gibbs free energies of formation

, the values of

and

can be easily determined. The heat capacity integrals on the right-hand side can be computed with the general expressions

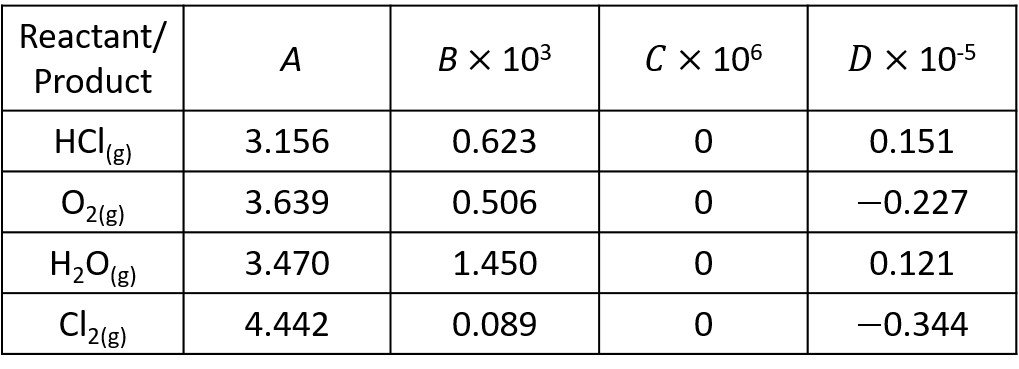

in which =

/

is the temperature ratio and the

‘s are, by definition,

Having evaluated all terms on the right-hand side of equation (III), the reaction change in Gibbs free energy and thence the equilibrium constant

can be established. Lastly, the extent of reaction and thence the molar fractions can be determined with equation (II). The steps are summarized below.

Step 1. With the initial number of moles and stoichiometric coefficients, determine expressions for the molar fractions using equation (I).

Step 2. Substitute the molar fractions into equation (II) to determine an expression that relates the extent of reaction to the equilibrium constant K.

Step 3. Determine the heat of reaction and the change in Gibbs free energy

at 298 K.

Step 4. Using the temperature ratio and the

coefficients, evaluate the heat capacity integrals.

Step 5. Using the results from steps 3 and 4, determine the right-hand side of equation (III).

Step 6. Knowing that , determine the equilibrium constant K.

Step 7. Substituting K in the expression determined in step 2, determine the extent of reaction .

Step 8. Substitute in the expressions derived in step 1 and determine the mole fractions.

We now present two applied examples.

Example 1

The following reaction reaches equilibrium at 500ºC and 2 bar:

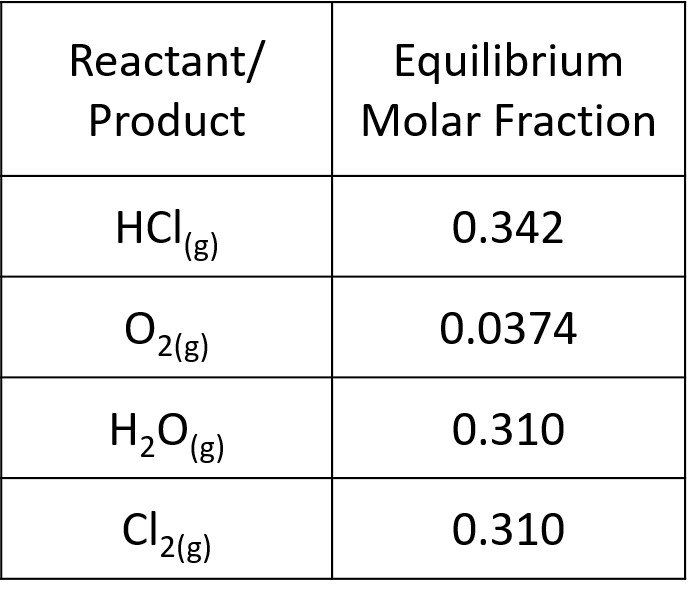

If the system initially contains 5 mol of HCl for each mole of oxygen, what is the composition of the system at equilibrium? Assume ideal gases. Use the following data.

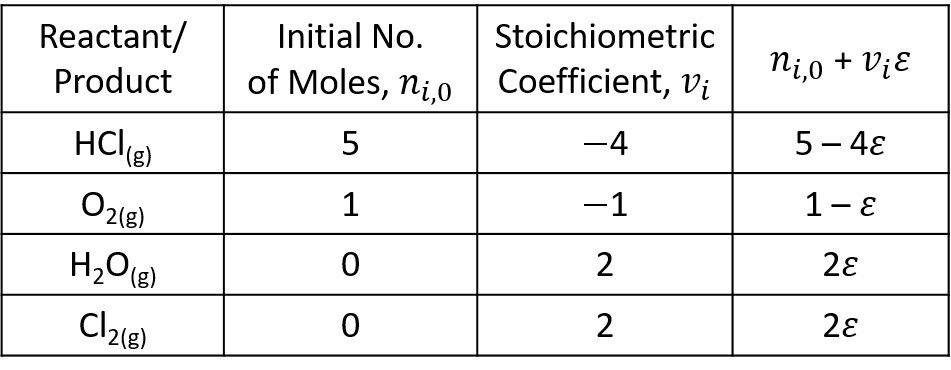

The molar balance is outlined below.

The total No. of moles at the beginning of the reaction is

The product of reaction stoichiometric number and extent of reaction is

The mole fractions of each component are written next.

The equilibrium constant, pressure, and composition are related by equation (II),

Substituting the molar fractions, = 2 bar,

= 1 bar, and

= -1 gives

It remains to compute the equilibrium constant K. In step 3, we calculate the heat of reaction at 298 K,

and the change in Gibbs free energy at 298 K,

Next, we compute the coefficients for use with the heat capacity integrals.

Now, the temperature ratio is = 773/298 = 2.59. In step 4, we evaluate the enthalpy integral

and the entropy integral

We now have all the information necessary to calculate . Indeed,

Resolving the logarithm,

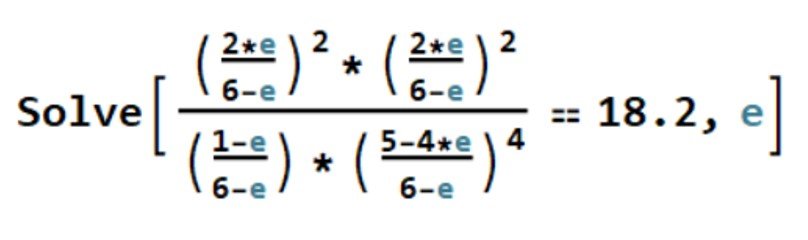

Substituting in equation (IV) yields

Adjusting the fraction on the left-hand side, we have

The equation above is a fifth-degree polynomial in and does not lend itself to elementary methods of solution. One way to go is to apply Mathematica’s Solve command,

This returns four imaginary solutions and = 0.806, which is a valid result. The extent of reaction has been determined. It remains to compute the molar fractions, namely

The sum of molar fractions is such that

as it should be. The slight difference is due to roundoff. Our results are tabulated below.

Example 2

Oil refineries frequently have both and

to dispose of. The following reaction suggests a means of getting rid of both at once:

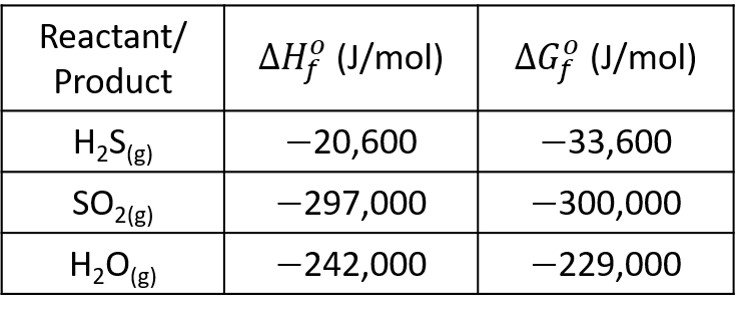

For reactants in the stoichiometric proportion, estimate the molar fraction of each reactant if the reaction comes to equilibrium at 450ºC and 8 bar. Use the following data.

The sulfur exists pure as a solid phase, for which the activity is /

. Since

and

are for practical purposes the same, the activity is unit, and it is omitted from the equilibrium equation. Having established this, we turn to the molar balance of the three other species involved in the reaction.

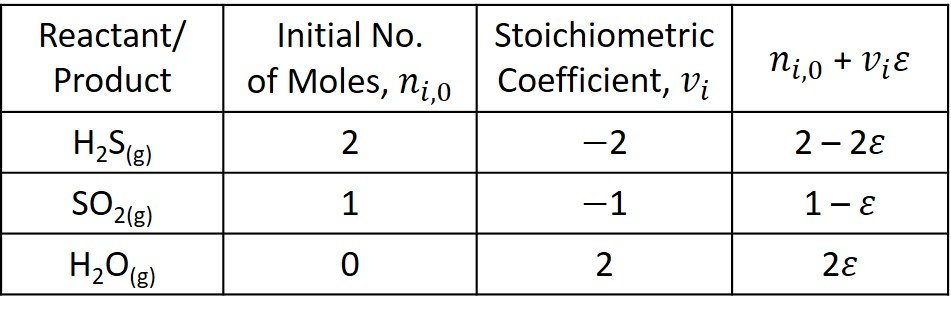

The total No. of moles at the beginning of the reaction is

The product of reaction stoichiometric number and extent of reaction is

The mole fractions of each component are written next.

The equilibrium constant, pressure, and composition are related by equation (II),

Substituting the molar fractions, = 8 bar,

= 1 bar, and

= -1 gives

The heat of reaction at 298 K is

and the change in Gibbs free energy at 298 K is

Next, we compute the coefficients for use with the heat capacity integrals.

Now, the temperature ratio is = 723/298 = 2.43. In step 4, we evaluate the enthalpy integral

and the entropy integral

We can now establish the value of ,

Resolving the logarithm,

Substituting in equation (V) yields

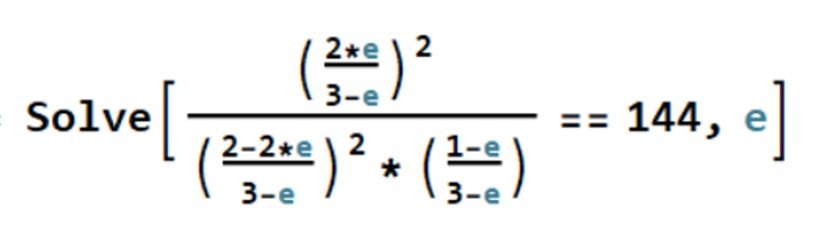

As before, we can solve the ensuing equation with Mathematica’s Solve command,

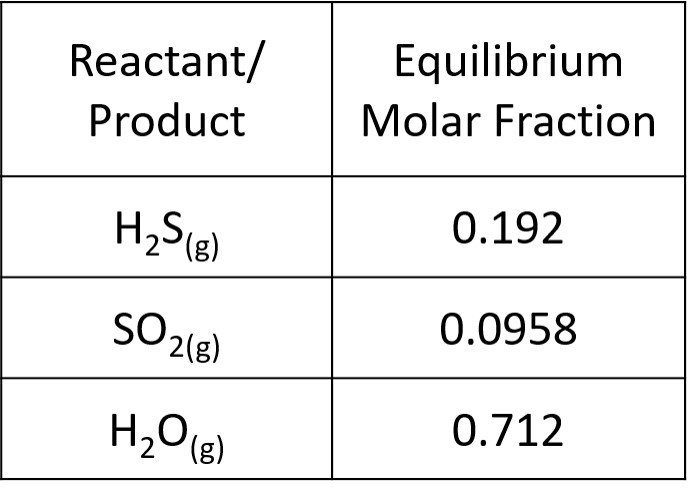

This returns two imaginary solutions and = 0.788, which is a feasible result. The extent of reaction has been established. Lastly, we can determine the equilibrium mole fractions,

The sum of molar fractions is

as one would expect. The results are summarized below.

Reference

• SMITH, J., VAN NESS, H. and ABBOTT, M. (2004). Introduction to Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics. 7th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.